FIELD NOTES: SHARING BEST PRACTICE

Beneath Our Feet Lies the Future: Why Soil Health is Key to Resilient Gardens, Parks, and Green Communities

Understanding Soil in our gardens

“A soft symphony of sounds emanates from the soil within a forest and the more thriving the ecosystem, the greater the diversity of noise.”

New Scientist

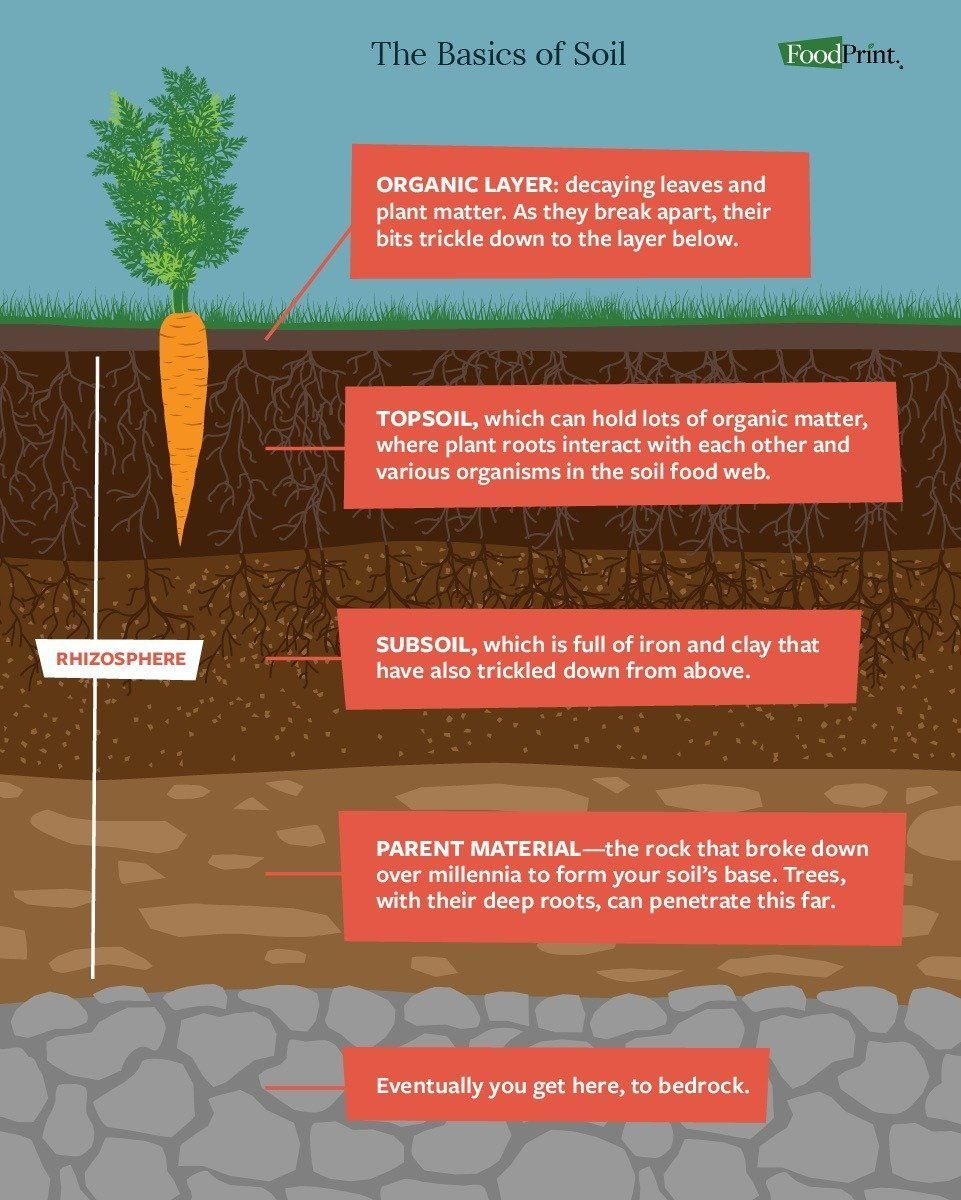

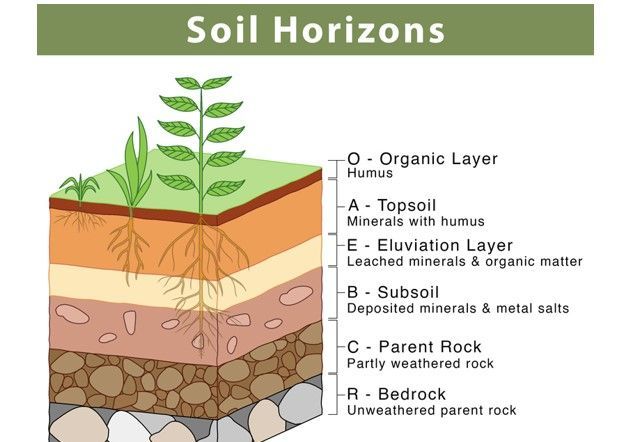

Only early succession plant life will be supported above ground if the microherd is predominantly bacteria. If you have frequently disturbed, compacted or poisoned ground or a garden with minimal organic matter, it will mostly support ‘weeds’, wildflowers and some pioneer shrubs. In a brownfield garden with minimal topsoil the plants grow ‘hard’ and will be tough, often very floriferous and still excellent for pollinators but not for mammals that need higher nutrient food plants. These gardens have early succession soils as in the diagram below.

Many agricultural soils that have been over-tilled, weedkilled and over-fertilised are also highly bacterial and low in other available nutrients. If they have too much manure, they may be very rich but rich in bacteria – what soil guru Nicole Masters calls ‘constipated soil’.

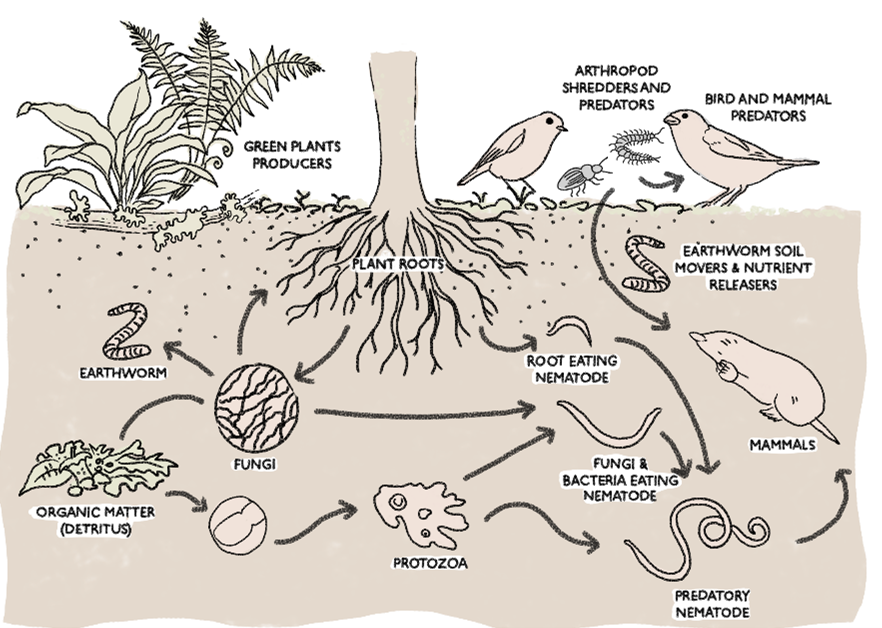

The nutrients can’t get from the soil to the plant without the protozoa nematodes and microarthropods, so farmers rely on artificial inputs like chemical nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) to feed the crop. How much cheaper it would be to create the conditions for healthy roots and allow the plant and a fully diverse herd of microbes to gather what they need.

How does our soil biology impact our gardens on a practical level?

To answer this, let’s look below ground. To have a fully functioning soil microbiome we need enough bacteria, fungi, protozoa and nematodes to feed plants, in the proportion for the type of plants we want to grow, and to minimise the microbes that will harm our plants.

A soil that is in an early succession phase through being disturbed or damaged is highly bacterial. Bacteria are the early clean-up crew, eating simply and multiplying rapidly. If the soil microbes are more in balance there will also be plenty of protozoa, amoebae and nematodes further up the food chain, and lots of fungi. A typical vegetable garden needs as much fungi in the soil as bacteria, at least 135 micrograms of each per gram of soil.

As the plants above ground become more complex and woody, these plants will thrive in more fungal-dominated conditions, wanting a balance of between 1:100 and 1:500 bacteria: fungi for shrubs and a whopping 1:50,000 for old growth forest (see chart below).